Red Hugh O’Donnell, Niall Garbh O’Donnell and the Siege of Donegal Abbey

It was the early morning of the 19th of September 16011 and the day promised to be another difficult one for the soldiers of the beleaguered garrison at Donegal Abbey, which overlooked Donegal Bay. The garrison was made up of English captains and soldiers, and Irish troops under Niall Garbh O’Donnell, who had defected to the side of the Tudor government the previous year. The thoughts of the soldiers must not have strayed too far from food as the garrison’s supplies were regularly low and the men were suffering. They could not search for food in the surrounding area as they were hemmed in by a besieging force under Red Hugh O’Donnell, a local chieftain who was one of the main leaders of a nationwide Gaelic confederacy that opposed the Tudor administration in Ireland. Red Hugh was also a bitter rival of Niall Garbh, and their rivalry was another iteration of a decades-long feud between two branches of the O’Donnells. The lack of food and cramped conditions meant sickness was rife among the soldiers; consequently, the garrison was left undermanned and in desperate need of reinforcements. Adding to the woes of the soldiers were the frequent skirmishes with the enemy. At Donegal Abbey, the sick and hungry soldiers starting their day could be forgiven for thinking that things could not get much worse but as smoke and flame became visible, that illusion would be broken. The panic must have been palpable as the soldiers rushed to put out the flames and move the barrels of gunpowder out of harm’s way. Their frantic attempt to remove the barrels proved futile as they caught fire, and a devastating explosion followed. Red Hugh soon became aware of the chaos at the Abbey and saw a golden opportunity to dislodge the troublesome garrison and perhaps even get rid of his foe, Niall Garbh, permanently . Red Hugh gathered his forces quickly and got ready to attack. The siege of Donegal Abbey was now entering its most pivotal and dramatic stage. This article will examine the 1601 siege of Donegal Abbey and the events leading up to it. First I will explain the background of the rivalry between the two main protagonists of the siege, Red Hugh O’Donnell and Niall Garbh O’Donnell.

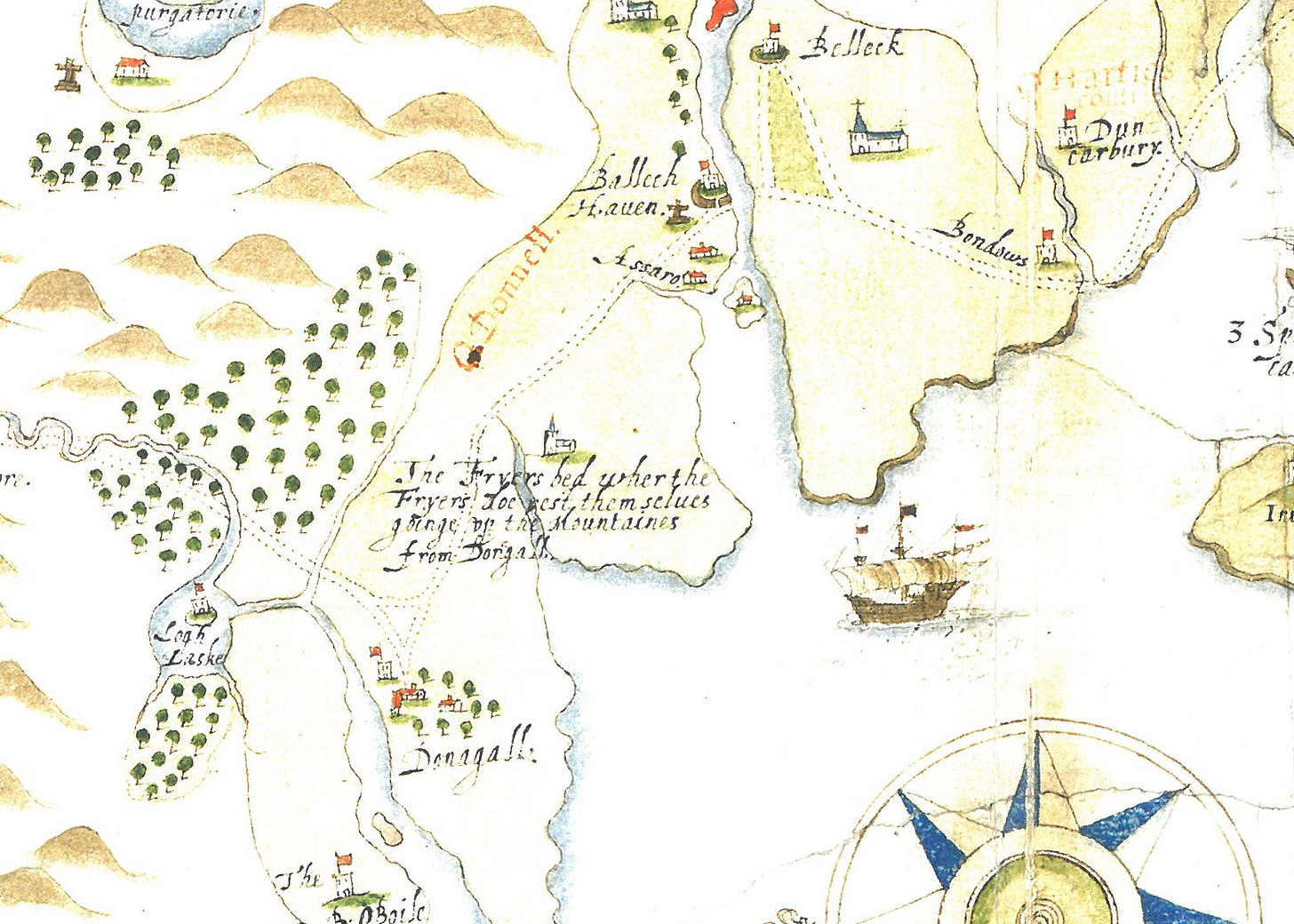

The origins of the feud date back to the 1560s and the death of Niall Garbh’s grandfather Calvagh O’Donnell. Calvagh O’Donnell was the chieftain of the O’Donnells, who controlled Tyrconnell. Tyrconnell was located in the northwest of Ireland and roughly consisted of the modern county of Donegal. In 1566 Calvagh died after falling from his horse. Calvagh was replaced by his brother, and father of Red Hugh O’Donnell, Hugh McManus O’Donnell.2 However, Calvagh’s son, Con, also wanted to be chieftain and he had a strong claim under English law because Calvagh had received letters patent from the English government. These letters patent granted Calvagh and his heirs Tyrconnell. Therefore, Con, as Calvagh’s eldest son, was entitled to Tyrconnell and Hugh McManus could be seen as a usurper. This was the opinion of the Archbishop of Cashel, Miler Magrath, who stated in 1592 that Hugh McManus had ‘usurped’ the Tyrconnell lordship from Con and his descendants.3 In 1566 Con was not in a position to stake his claim for the chieftainship following his father’s death because he was being held captive by a Shane O’Neill but once he was released there was, as Lord Deputy Henry Sidney pointed out, ‘great likelihood of great wars’ between Hugh McManus and Con over control of Tyrconnell. To prevent this, Sidney intervened and acted as an arbitrator. An agreement between the two was reached in which Con was given the castles of Lifford and Finn and lands that amounted to about a third of Tyrconnell.4 Con was also made tánaiste which was heir or designated successor. In return Con agreed to recognise Hugh McManus as chieftain and hand over to him other castles in his possession such as Donegal castle.5

Sidney’s mediation avoided a war and established Con as a second power bloc in Tyrconnell. For the Tudor administration in Ireland, having Con act as a counterpoise to the O’Donnell chieftain would be seen as potentially very beneficial if Hugh McManus proved to be disloyal. The Irish council pointed out this benefit in a letter to Elizabeth I. The council stated that if the O’Donnell chieftain ‘be found unfaithful to your highness’ then ‘in our opinions the maintenance of Con O’Donnell against him [Hugh McManus]…..would avail to O’Donnell’s annoyance’.6 The accord negotiated by Sidney did not end the rivalry between the two O’Donnells because, for the next decade and a half, tensions remained. In 1576 Sidney once again had to intervene to prevent violence between the two ‘mortal enemies.’ Sidney’s intervention led to the two men coming to another agreement in which Con’s possession of Lifford and position as tánaiste was reaffirmed. Sidney claimed that the two rivals departed as ‘good friends’ and it is possible that Hugh McManus and Con did try to genuinely reconcile in the late 1570s.7 This attempt at a sincere reconciliation is evidenced by a foster arrangement. Hugh McManus’s son, Red Hugh O’Donnell, was fostered with Con O’Donnell and given that Red Hugh was born in 1572 and Con died in 1583, it is likely that this fosterage took place during the late 1570s.8 Red Hugh and Con’s son, Niall Garbh were thus foster brothers. Fosterage was very important in Gaelic Ireland and it could produce a strong lifelong bond between a foster child and their foster family, so much so that foster children were said to be closer to their foster family than their blood relatives. Sir John Davies, Attorney General of Ireland, made a note of this strong bond and stated that fosterage ‘hath always been a stronger alliance than blood, and the foster-children do love and are beloved of their foster-fathers and their sept more than of their own natural parents and kindred, and do participate of their means more frankly, and do adhere unto them in all fortunes with more affection and constancy.’9

Sidney’s interventions and Con fostering Red Hugh was not enough to prevent violence between the two contenders for Tyrconnell. In the summer of 1581, Con and his close ally, Turlough Luineach O’Neill, inflicted a heavy defeat on Hugh McManus in a battle near Raphoe. Turlough Luineach claimed that Hugh McManus’ casualties were as high as 600 but the O’Donnell chieftain maintained that he only lost 80 men. Vice treasurer Henry Wallop thought Turlough’s estimate was ‘more the truth than the other’.10 Con’s desire for Tyrconnell and the O’Donnell chieftainship appears to be the driving force behind this renewal of hostilities. This was the opinion of Lord Deputy Arthur Grey who blamed Con’s ‘ambition and desire’ to be chieftain for the outbreak of conflict.11 Grey and the Irish council would also state that Con was the ‘only cause of the quarrel.’12 Hugh McManus’ defeat at Raphoe was bad enough that he needed to ask Tudor government officials in Dublin for help and there were serious concerns among these crown officials that he would be completely overthrown by the Turlough-Con coalition. At this point Hugh McManus was seen as a loyal subject, while Turlough was viewed as dangerous so the Dublin government wanted to avoid Hugh McManus’ overthrow and restrain the troublesome Turlough. To curb Turlough and his ally Con, Lord Deputy Arthur Grey organised a two-pronged attack. Forces under Nicolas Malby were sent from Connacht to Tyrconnell and the Lord Deputy himself went to the Blackwater in Armagh. This was enough to intimidate Turlough, who, after some talks with government officials, agreed to refrain from using violence towards Hugh McManus.13 This only gave Hugh McManus a brief respite as the following year he was once again under pressure from Con and Turlough and was, according to Malby, ‘utterly undone.’14 Con was in such a strong position that he was able to invade north Connacht, where he looked to impose the O’Donnells’ traditional claim of overlordship. Furthermore, Con was now so dominant that his men referred to him as the O’Donnell,15 a title that Con said he would have in spite of the whole world.

Con died in 1583 but his death only temporarily abated the threat of the descendants of Calvagh as their cause was next taken up by Hugh McCalvagh O’Donnell, a ‘supposed base son’ of Calvagh O’Donnell. Originally he was known as Hugh O’Gallagher and believed to be the son of the dean of Raphoe but later in life he claimed to the progeny of Calvagh O’Donnell.16 Hugh McCalvagh was a real threat to Hugh McManus’ control of Tyrconnell. In fact in 1587 Hugh O’Neill, the earl of Tyrone and a son-in-law of Hugh McManus, claimed that Hugh McCalvagh was so powerful that he had almost forced Hugh McManus out of Tyrconnell.17 The fortunes of Hugh McManus deteriorated further in May 1588 when he and his ally, Hugh O’Neill, were soundly defeated by Turlough Luineach O’Neill and Hugh MacCalvagh at Carricklea.18 Hugh McCalvagh may have been able to gain control of Tyrconnell if it had not been for Hugh McManus’ wife, Fiona MacDonnell. She was known as Inion Dubh and was the daughter of James MacDonnell of Dunyveg. This connection to Scotland gave her access to Scottish mercenaries and a contingent of them were said to be ‘constantly in her service and pay, and who were in attendance on her in every place’.19 She was determined that her son Red Hugh succeed his father as chieftain but her plans suffered a setback when Lord Deputy John Perrot organised the kidnapping and imprisonment of the young Red Hugh in 1587. Red Hugh was held in Dublin Castle and during his confinement, Inion Dubh worked hard to make sure her son’s path to the chieftainship would be clear when he returned. She eliminated those who might block her son’s succession and in 1588 she was able to get rid of Hugh McCalvagh. Shortly after Carricklea, Hugh McCalvagh happened to pass through Mongavlin, where Iníon Dubh’s chief residence was. She heard that he was in the vicinity and sent her Scottish bodyguards to assassinate him. They rushed to do her bidding and when they encountered Hugh McCalvagh, they ‘proceeded to shoot at him with darts and bullets, until they left him lifeless’.20

Inion Dubh’s interventions meant that when Red Hugh O’Donnell escaped from Dublin Castle and returned to Tyrconnell in 1592, he was able to replace his father, who resigned his position as chieftain in favour of his son. Red Hugh was inaugurated as O’Donnell chieftain at the traditional inauguration site at Kilmacreanan but there were a few notable disgruntled absentees. One of these absentees was Niall Garbh O’Donnell, Con O’Donnell’s eldest living son. The previous year there had been an attempt to mend the rift between the two families through a marriage as Niall Garbh married Red Hugh’s sister Nuala.21 Therefore Red Hugh and Niall Garbh were foster brothers and brothers-in-law. However, Niall’s decision to shun Red Hugh’s inauguration demonstrated that the marriage did little to diminish the succession dispute as Niall Garbh’s absence clearly conveyed that he still desired Tyrconnell and opposed the new chieftain. Niall Garbh was not strong enough to resist Red Hugh for long and eventually he acknowledged Red Hugh as the new O’Donnell chieftain. Red Hugh O’Donnell’s biographer Lughaidh Ó Cléirgh, noted that Niall Garbh did not accept Red Hugh as chieftain because of any affinity towards him but rather Niall acquiesced to his rival ‘wholly through fear’.22

The Nine Years’ War would begin in early 1593 when Hugh Maguire rebelled after Humphrey Willis took up the post of sheriff of Fermanagh and alienated the locals through pillaging their lands. The war was a conflict between the English crown government in Ireland and a Gaelic confederacy headed by Hugh O’Neill and Red Hugh O’Donnell. Red Hugh would openly enter the war in May 1594 when he took part in a siege at Enniskillen. At this stage Red Hugh was still suspicious of Niall Garbh and early in 1594, the O’Donnell chieftain decided to imprison his dangerous rival. Niall would be released but not before Red Hugh received Niall Garbh’s brother as a hostage.23 While Niall Garbh’s loyalty may have been suspect, there was little doubt about his ability as a military commander. Lughaidh O’Cleirgh, even though he was hostile to Niall Garbh, begrudgingly admitted that he ‘was a hero in valour and fighting.’24 Henry Docwra would state that Niall Garbh was seen as ‘valiant and hardy as any man living’.25

Red Hugh must have also viewed Niall Garbh as a brave and skilled military leader because Red Hugh would often give Niall Garbh command of his forces when he was absent. For example, at a siege at Collooney in the summer of 1599, Niall Garbh was put in charge of the besieging force after Red Hugh left for the Curlew Mountains where he and his allies repelled a relieving army under the President of Connacht, Sir Conyers Clifford.26 However, Niall Garbh had not given up his ambition of becoming O’Donnell chieftain and would turn against Red Hugh if given the opportunity. This was evident in Art O’Neill’s communications with the crown government. Art was an ally of Niall Garbh and rival of Hugh O’Neill. Art hoped to defect to the crown government’s side if an English army landed at Lough Foyle and he made this fact known to English authorities. In his dealings with the English, Art also insisted that Niall Garbh would ally with the Tudor government if he was granted Tyrconnell in return.27 In May 1600 Sir Henry Docwra and a force of 4000 men arrived at Lough Foyle and quickly establish garrisons at Culmore, Elagh and, most importantl,y at Derry. On October 3rd 1600, Art’s prediction that Niall Garbh would defect was proved correct as he arrived at the Derry garrison and pledged allegiance to Docwra and the Queen. He would subsequently be assured that he would get Tyrconnell as compensation for his defection and assistance.28 When Niall Garbh defected, Red Hugh was leading an army into Connacht to carry out raids and he had enough faith in Niall Garbh’s loyalty that he left him in charge of besieging the garrison at Derry. When Red Hugh heard of Niall Garbh’s defection, his reported shock highlights how badly he had misjudged Niall. According to Captain Humphrey Willis, when Red Hugh ‘heard of Neale Garve's coming in, he was so dumbstricken, that he did neither eat nor drink in three days’ and Ó Cléirigh stated that Red Hugh ‘wondered greatly, and was surprised that one who was kinsman and brother-in-law should turn against him.’29

Niall Garbh’s defection and his assistance came at an opportune time for Docwra as the Lough Foyle expedition was in desperate need of help. It was poorly supplied and suffering badly from disease. Sickness and morality were so bad that Docwra claimed that ‘it is hard to conceive to one that hath not seen it’. A hospital was built to help alleviate the situation, but Docwra thought it could do little to ease suffering because ‘how small a drop of water all this hath been, in respect of the seas of sick men that daily increased.’ The poor conditions also meant many deserted and Docwra complained that ‘English men as well as Irish daily ran to the rebel’.30 The circumstances at the Lough Foyle garrisons were so dire that the expedition was practically immobilised. Lord Deputy Charles Blount, the 8th Baron Mountjoy, noted this lack of activity and bitterly complained to Sir Robert Cecil of the ‘little stirring or effect of Lough Foyle, that have lost the use of 4000 men’.31

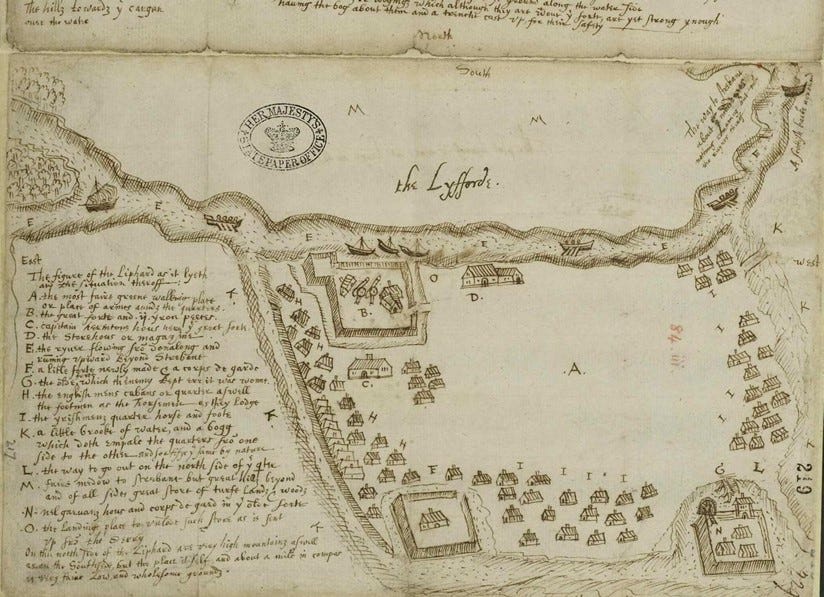

The Lough Foyle expedition’s inertia would be broken by Niall Garbh. On 8th October Niall urged Docwra to take Lifford before Red Hugh, who had just returned from Connacht, could reach it. Docwra agreed and sent 500 foot and 30 horse under the command of Sir John Bolles to assist Niall in seizing Lifford. Lifford was lightly defended so Niall and government forces were able to quickly capture it on 9th October. The ward of about thirty men were put to the sword, with Niall said to have killed six men personally.32 Red Hugh quickly responded and encamped near Lifford. Over the next month there were a number of skirmishes between him and the garrison. The most notable occurred on the 24th October when Red Hugh’s forces tried to burn some of the garrison’s turf. Niall Garbh and the Lifford garrison responded by sallying out and charging at Red Hugh, Niall and his brothers took the vanguard. Red Hugh’s forces were repulsed and, in the fight, Niall remained in the thick of the action. He killed Red Hugh’s younger brother Manus and barely escaped with his life. According to Docwra, Niall Garbh was struck three times with a ‘staff’ but his chainmail seems to have prevented serious injury. His horse was also ‘shot in the body and head under him’.33 For Docwra, Niall’s actions at Lifford meant his loyalty was assured and Docwra told Robert Cecil this when he wrote that they ‘needed no better hostages for his fidelity’ than the killing ‘with his own hands (in fight and open view of our men that saw him) O'Donnell's second brother.’ Docwra also thought after events at Lifford, Niall Garbh and Red Hugh could not reconcile as their hatred for each other was too great.34

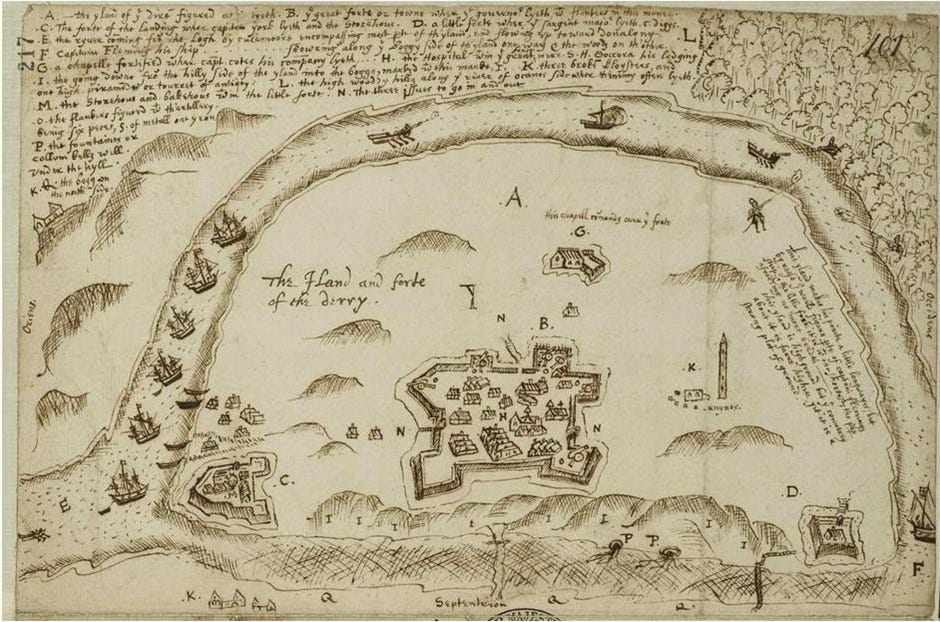

By taking Lifford and expanding the crown forces’ presence in Tyrconnell, Niall Garbh took pressure off Docwra and his Derry garrison as they were no longer the focal point for Red Hugh and Hugh O’Neill’s forces. Consequently, as Ó Cléirigh put it, Niall’s taking of Lifford had ‘released them [the English] from the narrow prison in which they were.’35 Niall Garbh would continue to serve Docwra and the crown for the rest of 1600 and into the summer of 1601. One of his most important contributions was providing Docwra and his forces with guides and intelligence. Docwra was deep in enemy territory, ignorant of the local landscape and had no accurate map. Thus he needed local allies like Niall Garbh who could supply guides and intelligence. Without either Docwra would have achieved little and after the war he acknowledge this, confessing that without his Irish allies and their ‘intelligence & guidance little or nothing could have been done of our selves’.36 Niall Garbh was also very active in the field, attacking the lands and forces of both O’Neill and Red Hugh on several occasions. Niall Garbh continued to help expand Docwra and the crown’s presence in Tyrconnell as garrisons were established at Castlederg, Ramelton and Rathmullan. However, Red Hugh was still relatively untouched in south Tyrconnell but that would change in August 1601 when Docwra sent Niall Garbh and 400 English soldiers to Donegal, where they occupied Donegal Abbey. Docwra soon sent reinforcements so the fighting force on paper was 650 English soldiers, who were supplemented by Niall Garbh’s Irish contingent.37

Red Hugh was in north Connacht so he could not prevent Niall and his English allies from occupying Donegal Abbey but, by the end of August, he had returned to Tyrconnell and began besieging the garrison at Donegal.38 Red Hugh was able to capture 100 of the garrison’s cows, which the garrison could ill afford to lose as they were suffering from deprivations, especially food.39 In a letter to the English Privy council Docwra highlighted the poor food situation at Donegal, stating that the garrison there endured ‘hardness and misery….. for want of natural food’.40 Docwra did send supplies via the sea but the boat was late arriving because of contrary winds. The harsh conditions meant the forces at Donegal were greatly weakened and it was so bad that by the 2nd of September, Docwra estimated that out of the 650 English soldiers with Niall Garbh only 150 were fit for service. Docwra tried to help by sending reinforcements to the beleaguered garrison, but Red Hugh’s much larger army caused Docwra to abandon the effort.41 Irish sources also paint a bleak picture of the circumstances of the Donegal garrison. For example, The Annals of the Four Masters stated that

The English were reduced to great straits and distress by the long siege in which they were kept by O'Donnell's people; and some of them used to desert to O'Donnell's camp in twos and threes, in consequence of the distress and straits in which they were from the want of a proper ration of food.42

The desertion mentioned by the annals does appear to have been an issue as evidenced by a letter sent by Niall Garbh to Docwra. In the letter Niall complained that four of his horsemen had gone over to Red Hugh. There was also regular fighting between the two sides. A few days after Red Hugh arrived, Niall Garbh stated that the two sides had fought every day and the previous day he claimed they killed six or seven of Red Hugh’s men and wounded a further twenty who Niall thought were unlikely to recover. Niall did not elaborate on his losses except for a brief mention that four or five of his horses were shot and killed.43 During the siege Niall Garbh and Red Hugh did have talks. However, Niall Garbh was negotiating in bad faith as he never intended to reconcile. Instead, Niall Garbh kept Docwra informed of proceedings and had his permission. Niall’s plan was to convince Red Hugh to hand over a castle at Lough Eske and then Niall would give it to Docwra and his crown forces.44

While Niall and his English allies were suffering Docwra was prospering, thanks in part to the Donegal garrison. With Red Hugh distracted by Niall Garbh at Donegal, Docwra was left largely unchallenged in the north of Tyrconnell. This allowed him and his forces to destroy much of the harvest and take many cows, to the extent that much of Tyrconnell was uninhabited and wasted with Docwra confident that there would be a famine next year. Docwra gave the Donegal garrison full credit for his success as he conceded that he would not have accomplished what he did ‘if so great a number of that rebellious body had not been kept off by that garrison.’45

Back at Donegal, on 19th of September the most dramatic event of the siege happened. A fire broke out at the Abbey, whether it was an accident or on purpose it was never determined. A strong wind meant that the fired spread and the occupiers of the Abbey desperately tried to remove their supplies to safety, especially the dangerous barrels of gunpowder. They failed and the barrels caught fire. This caused an explosion which killed and wounded many of the garrison as well as destroying much of their food, gunpowder, money, beds and other supplies.46 Ó Cléirigh gave a vivid and probably somewhat hyperbolic description of the destruction wrought by the explosion. Ó Cléirigh wrote that the explosion caused;

The stones and the wood and the men, wholly and completely, without any separation of their bodies, were mixed up in flight and hovering above for a long time, and they fell on the ground charred corpses, and some of them fell on the heads of the people beneath them when coming back to earth.47

Once Red Hugh took notice of what happened, he attacked the Abbey and the focus of his attack was a storehouse where food was kept. His men managed to capture part of the storehouse and a fierce fight ensued. According to Ó Cléirigh and other Irish sources, Niall Garbh saw that they were about to be overrun so he slipped away and fled to an English garrison at Magherabeg Friary, a quarter a mile south of Donegal. Niall Garbh returned with English soldiers from Magherabeg and Red Hugh, perceiving that he was about to be overwhelmed by these reinforcements, decided to retreat.48 Niall Garbh in his letters to Docwra does not mention escaping to Magherabeg nor do the English at Donegal reference it so it probably did not happen. Both Niall and the English do note that there was an intense battle at the storehouse and Red Hugh’s forces were eventually repelled and forced to retreat. For example, John Forth was present at the battle and stated that Red Hugh’s forces managed to capture the walls of the storehouse but ‘with [a] long and dangerous skirmish they were driven back’.49 Niall Garbh in a letter to Docwra reported that it was ‘with much travail and a long fight we beat him back again when they had gotten and maintained the wall of the storehouse.’50 Estimates of the casualties vary. According to Ó Cléirigh the English lost 300 men.51 However, Captain Paul Gore claimed that among the English companies, 27 soldiers, 3 sergeants and a captain were killed.52 Niall Garbh lost 16 of his men in the explosion and subsequent fighting, most notably his brother Con Og.53 That means that 47 were killed. Docwra approximated that Red Hugh’s losses were about 60 men.54

While Niall Garbh and his English allies survived the attack, they were not clear of danger as the loss of provisions and supplies meant that the garrison was on the verge of collapse. These dire circumstances are evident in a letter from John Forth to Docwra. Forth told Docwra that they lost much of their munitions, food, tools and beds. They also lost £200. Forth begged Docwra to send ‘all necessary provisions so speedily as possible you may, for otherwise we are like to be in a most dangerous and miserable case’.55 Red Hugh, sensing the poor state of the garrison, sent a messenger who offered Niall Garbh and the English the opportunity to depart. While their situation was poor the garrison still had access to the sea and the prospect of supplies arriving via a boat. Therefore, they violently rebuffed the messenger. Niall Garbh and his English allies were given a reprieve because Red Hugh soon lifted his siege. The impetus for this was the arrival of a Spanish army at Kinsale.56 Red Hugh and Hugh O’Neill travelled to Kinsale to assist their Spanish allies but they suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of Lord Deputy Mountjoy. Red Hugh decided to go to Spain and intreat with the Spanish King to send another Spanish army to Ireland but his time in Spain was cut short as he died in September1602.

Niall Garbh reaped little reward for his service for the crown. His time with the English was marred by disagreements and tension. Niall was frustrated because he thought that he was not properly compensated by the English and that they restricted his authority in Tyrconnell. The English never fully trusted Niall Garbh and thought he was greedy, uncivilised and impetuous. Niall Garbh was implicated in the rebellion of Cahir O’Doherty in 1608 and imprisoned in the tower of London until his death in 1626.

Both Niall Garbh and John Forth say that the fire began in the morning. See Calendar of State Papers, Ireland, Vol.11, pp.98-9 (Henceforth CSPI). See link below

https://archive.org/details/1912calendarofstatep11greauoft/page/98/mode/2up?view=theater&q=morning

However, Sir Henry Docwra later claimed that the fire broke out at night in his A Narration of Services Done. The former seems more plausible as Niall Garbh and John Forth were writing in the immediate aftermath of the event while Docwra was writing over a decade after the siege of Donegal Abbey

Lord Deputy Sydney to the Privy Council, 18th January 1567, Kilmainham, SP 63/20/f.34,35

CSPI Vol.4, p.498, see link below

https://archive.org/details/calendarofstatep04greauoft/page/498/mode/2up?q=usurped&view=theater

Brady, Ciaran (ed), A Viceroy's Vindication?: Sir Henry Sidney's Memoir of Service in Ireland, 1556- 1578. Cork, Ireland: Cork UP, 2002, p.56

A friend to Sir W. Fylzvjylliams. 13th September 1567, Drogheda, SP 63/21/no.203

Lords Justice Weston and Fitzwilliam and Council to Queen Elizabeth, 30th October 1567, Dublin, SP 63/22/f.33

Lords Justice Weston and Fitzwilliam and Council to Queen Elizabeth, 23th January 1568, Dublin , SP 63/23/f.52

Sydney to the Privy Council. 15th June1576, Dublin, SP 63/55/f.165

Lughaidh Ó Cléirigh, Beatha Aodha Ruaidh Uí Dhomhnaill or The Life of Aodh Ruadh O Domhnaill (hereafter Beatha Aodha Ruaidh), 2 parts, ed and transl. Paul Walsh, (Dublin: Irish Texts Society), 1948, 1957, p.55

Beatha Aodha Ruaidh can be found on the CELT website. Link below

Davies, John. "A Discovery Why Ireland Will Never Entirely Be Subdued," in Henry Morley (ed) Ireland under Elizabeth and James the First. London: G. Routledge and Sons, 1890, p. 296. The passage is linked below.

https://archive.org/details/irelandundereliz00morl/page/296/mode/2up?q=fostering&view=theater

Wallop to Walsyngham, 17th July 1581, Dublin, SP 63/84/f.55

Annála ríoghachta Éireann: Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters, (hereafter AFM), 7 vols., ed. John O'Donovan (Dublin: 1851), s.a. 1581, https://archive.org/details/annalsofkingdomo05ocle_0/page/1764/mode/2up?view=theater

Lord Deputy Grey to the Privy Council. 12th August 1581, Dublin, SP 63/85/f.32

Articles by Capt W. Pers for the reformation of the North, postilled by the deputy and council. 10th August 1581, SP 63/85/f.17, See note 8 in the margin

Lord Deputy to the Queen, 10th August 1581, Dublin SP 63/85/f.10-3,

Lord Deputy Grey to the Privy Council. 12th August 1581, Dublin, SP 63/85/f.30-2,

The peace between the Lord Deputy and Council and Turlough Lynagh O'Neill. 2nd August 1581, SP 63/85/f.36-7

Sir N. Malbie to Walsyngham. 12th July 1582, Roscommon, SP 63/94/f.50

Ibid, folio 51

A chieftain of a clan was simply known by their surname. This would act as a formal title denoting him as the chieftain, a position that was also referred to as chief (or captain) of his name (or nation).

Carew Manuscripts Vol. 3, pp.152-3

https://archive.org/details/calendarofcarewm03lambiala/page/152/mode/2up?view=theater&q=base

A base son is a male child born to unmarried parents.

AFM, s.a. 1588

https://archive.org/details/annalsofkingdomo05ocle/page/1866/mode/2up?view=theater

The examination of John Benyon, 6th May 1588, SP 63/135/f.49-50

ibid

Jerrold Casway, “Women in Flight.” History Ireland, Vol. 15, No. 4, (July-Aug, 2007), p. 74

Can be accessed here

https://historyireland.com/from-the-files-of-the-dib-women-in-flight/

Beatha Aodha Ruaidh, pp.41, 55

James O'Neill, The Nine Years War 1593-1603: O'Neill, Mountjoy and the Military Revolution. Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2017, pp.33-4

Beatha Aodha Ruaidh, p.55

O'Neill's son to Sir Samuel Bagenall, 1599, SP 63/206/f.346

CSPI, vol.9, pp.380, 407

Kelly, William, (ed). Docwra's Derry: A Narration of Events in North-West Ulster, 1600-1604. Belfast, Ulster Historical Foundation, 2003, p.51

Beatha Aodha Ruaidh, pp.263-7,

CSPI vol.9, p.535

https://archive.org/details/1903calendarofstatep09greauoft/page/534/mode/2up?view=theater&q=dumb

CSPI vol.9, p.536

CSPI vol.10, pp.10-1

Beatha Aodha Ruaidh, p.271-3

CSPI vol.10, pp.10-1

Beatha Aodha Ruaidh, p.265

Kelly, Docwra's Derry: p.52

Sir Henry Docwra to the Privy Council of England, 2nd September 1601, Derry, SP 63/209 partt.1/f.132

ibid

CSPI vol.11, p.98

https://archive.org/details/1912calendarofstatep11greauoft/page/98/mode/2up?view=theater&q=esk

Salisbury Manuscripts, Vol. 15, pp.145-6,

https://archive.org/details/calendarofmanusc15grea_0/page/146/mode/2up?view=theater

Kelly, Docwra's Derry, p.60

John Forth, Commissary of the Victuals at Donegal, to Sir Henry Docwra, 24th September 1601, Donegal, SP 63/209/part 1, f.286

Neale Garve O'Donnell to Sir Henry Docwra, 26th September 1601, Donegal, SP 63/209/part 1, f.287

Beatha Aodha Ruaidh, p.307-9

Beatha Aodha Ruaidh, pp.309-11

O’Sullivan Beare, Philip. Chapters towards a History of Ireland in the reign of Elizabeth. Matthew Byrne (ed), Port Washington, Kennikat Press, 1970, pp.137-9

A1902 edition can be found here https://archive.org/details/irelandundereliz00osul/page/138/mode/2up?q=donegal

John Forth, Commissary of the Victuals at Donegal, to Sir Henry Docwra, 24th September 1601, Donegal, SP 63/209/part 1, f.286

Neale Garve O'Donnell to Sir Henry Docwra, 26th September 1601, Donegal, SP 63/209/part 1, f.287

Beatha Aodha Ruaidh, p.311

Captain Paul Gore to Sir Henry Docwra, 24th September 1601, Donegal, SP 63/209/part 1, f.285-6

Neale Garve O'Donnell to Sir Henry Docwra, 24th September 1601, Donegal, SP 63/209/part 1, f.285

John Forth, Commissary of the Victuals at Donegal, to Sir Henry Docwra, 24th September 1601, Donegal, SP 63/209/part 1, f.286

Kelly, Docwra's Derry, pp.60-1